Why does a book from 1999 still show a sauropod living in a swamp?

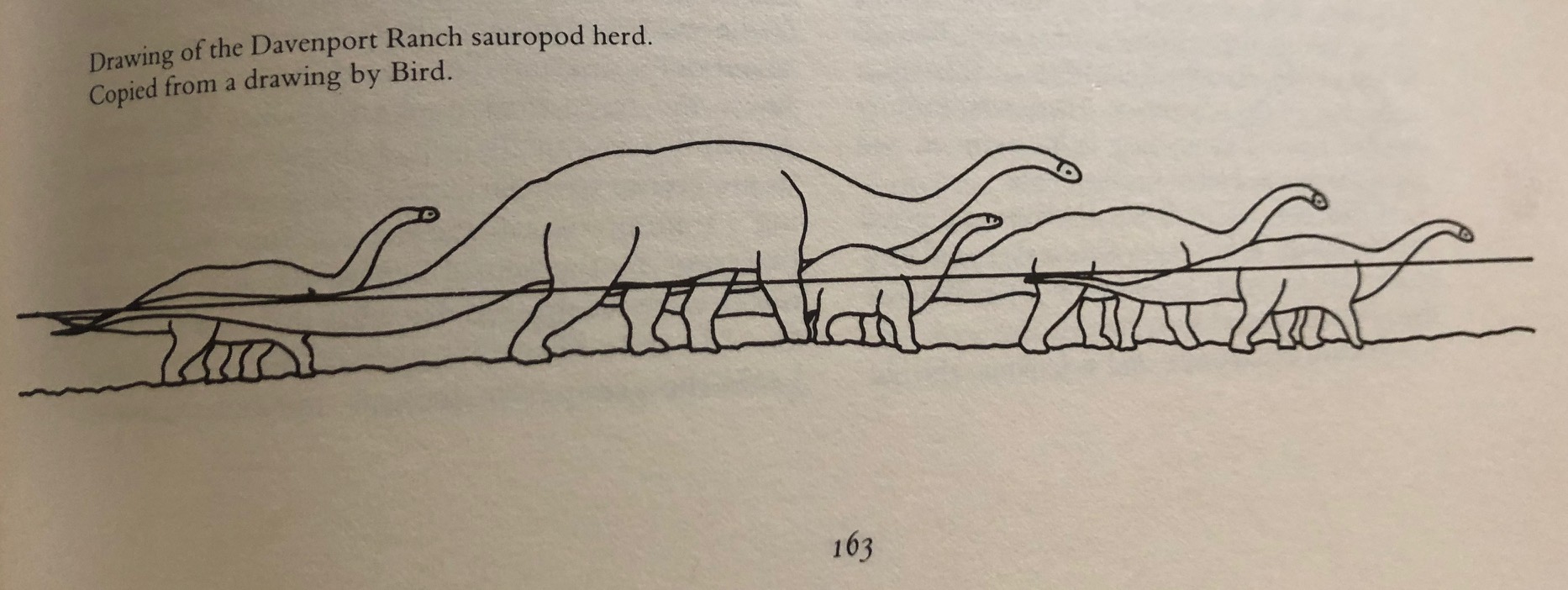

Illustration from Bones for Barnum Brown showing Bird’s sketch of the sauropod herd at Davenport Ranch.

In the spring, a curiosity blogger’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of dinosaurs. Specifically, the sauropod tracks in Glen Rose, Texas and whether this will be the summer I get to see them.

Thinking of the Glen Rose tracks inevitably reminded me of Roland T. Bird, who excavated them for the American Museum of Natural History back in 1939. (You can read Bird’s May 1939 account of prospecting for the tracks, “Thunder in His Steps,” in the online Natural History Magazine archives.)

Revisiting Bird’s 1939 article reminded me that I still haven’t found his 1944 essay, “Did Brontosaurus ever walk on land?”

I’d learned about this article, also published in Natural History Magazine, back in 2011, while researching whether sauropods could swim at my daughter’s request (at the time, she herself was struggling with swimming lessons, and was looking to the historical record for evidence to support the idea that wading was a “good-enough” life skill).

Although I never did find Bird’s original article online, I learned the substance of it from paleontologist Jeff Wilson’s secondhand summary. Apparently, Bird had argued in the article that the front-feet only trackways in Glen Rose had been made by a floating sauropod who was pushing himself along underwater by his front feet.

Although Bird’s idea has since been refuted, I would still like to read Bird’s arguments for myself. It occurred to me that now that we’re living in California, I’m connected to a different public library system. Their archives of the Natural History Magazine might go back further.

So I hopped online and searched the Northern California public library system’s catalog.

Sadly, their archives also appear to only go back about 20 years. Still, some of the outlying branches had a number of books on Roland T. Bird that I hadn’t read before, so I used the Interlibrary Loan service to send two of them hurtling in the direction of my local branch in the hopes that one of the books might include a reprint of that missing essay.

(Have you used your library’s Interlibrary Loan service yet? It transforms your little local branch into a regional information hub that makes the contents of every library in your state/regional public library system available to you. And as long as you don’t lose the book or return it late, the service is completely free. So fabulous.)

One of the books, The Dinosaur Footprints and Roland T. Bird, turned out to be a picture book from 1999 (guess I should have paid more attention to that little ‘J’ in its call number). But I read it anyway. You’d be surprised how much information gets packed into nonfiction picture books.

All was going well, until I came to the very last page, where I saw this:

To make matters worse, the caption in the picture book reads simply:

“Many of the giant footprints that Bird found were made millions of years ago by sauropods, such as this one.”

Look, I know this is Charles Knight’s classic 1897 painting, Brontosaurus.

And I know that it’s an iconic image that influenced popular culture’s perception of these giant beasts well into the 1960s. It’s true that in the 1930s and 1940s when Bird was working most actively with those sauropod tracks, he really did did think that sauropods spent most of their time in water. The other book I requested from Interlibrary Loan, Bones for Barnum Brown, is full of drawings like this one:

But The Dinosaur Footprints and Roland T. Bird was published in 1999. By then scientists had already spent decades agreeing that sauropods had likely spent most of their time on land.

Is it too much to ask that the caption tell young readers that we no longer think sauropods spent most of their time in water?

Or–hear me out–maybe you could include a simple artist credit and date for the painting itself somewhere other than in the buried photo credits for the book, which no parent would read to a five-year-old?

I mean, American wildlife artist Charles Knight (1874-1953) was a pretty amazing fellow in his own right. The sort of guy your child might want to read about sometime, especially since as one of the first people to illustrate dinosaurs, mammoths, and cavemen, Knight’s work is still a prominent feature of many natural history museums, including the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Want to learn more about Charles R. Knight?

Although I haven’t read it yet, Richard Milner’s extensively illustrated book, Charles Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time looks like a good place to start. In addition to reproductions of Knight’s famous and never-before-seen work, it includes a biography of Knight as well as several extracts from Knight’s writings about extinct and modern animals.

Sadly, it’s also well over $100 on Amazon, but I bet your local library has a copy. (Or if not, you can request one from a connected branch through their Interlibrary loan service.)

Bonus:

The second book I requested through interlibrary loan was Bones for Barnum Brown, Roland T. Bird’s own account of his time on Barnum Brown’s dinosaur hunting crew. Although it doesn’t include his 1944 essay either, Chapter 29 reads very much like Bird’s 1939 Natural History Magazine article, “Thunder in His Steps.” It’s almost word for word in places. And that gives me hope that Bird may have recycled some of his 1944 article to write Chapter 32, which discusses–among other things–how the front-foot only trackways might have been made.

Related Links:

- “Thunder in His Steps” by Roland T. Bird (Natural History Magazine archives)

- “Could sauropods swim?” (Caterpickles)

- “Why did they draw that sauropod underwater?” (Caterpickles)

4 Responses to “Why does a book from 1999 still show a sauropod living in a swamp?”

[…] “Why does a book from 1999 still show a sauropod living in a swamp?” (Caterpickles) […]

LikeLike

[…] for Barnum Brown: Adventures of a Dinosaur Hunter, delivered to my local public library through the Northern California Interlibrary Loan Service. So of course I did, hoping that it would include a reprint of his 1944 article, or at least a […]

LikeLike

[…] Watch an old movie or TV show featuring dinosaurs or read an old dinosaur book. […]

LikeLike

[…] Why does a book from 1999 still show a sauropod living in a swamp? (Caterpickles) […]

LikeLike