“How does a storm glass work?”: Part One, the Pondering

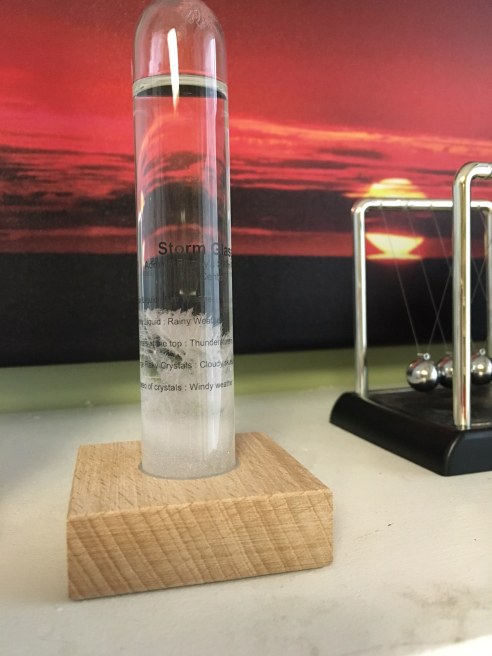

My storm glass forecast on January 25. The glare makes this a little hard to see, but the crystals reach to the words “19th Century” printed on the glass. (Photo: Shala Howell)

Several months ago, my daughter and I purchased a storm glass from a local science museum. It’s been sitting in the office making the same prediction ever since (according to the writing on the side of the glass, when large flaky crystals form, it means you are to expect cloudy skies and/or snow, if it’s winter).

To be fair, it is winter in Chicago, so yes. The sky is cloudy, and occasionally spits snow on us. In fact, as I type this, Chicago is having its longest stretch of cloudy skies in 25 years.

But our storm glass has been predicting cloudy skies since well before this current stretch began. I can’t be certain, but I think it’s been predicting cloudy skies ever since The Nine-Year-Old and I set up our retro weather center in the office six months ago.

The Caterpickles Central Weather Station. The storm glass is on the right, making its bold prediction of cloudy skies and possible snow in Chicago in winter. The glass tube on the left is Galileo’s thermometer. We’ll talk about how that guy works some other time. (Photo: Shala Howell)

The sameness of it all makes me think that the storm glass’s prediction says more about the conditions in my office than the weather outside.

Which got us wondering — how does a storm glass work anyway? But before we talk about that, let’s take care of some basics.

What is a storm glass?

In most cases,* a storm glass is a sealed glass tube containing a mix of ammonium chloride, potassium nitrate, camphor, distilled water, and alcohol.

In theory, the combination reacts to changes in the environment around it to form (and later dissolve) a variety of crystals. Paying attention to the types of crystals that form is supposed to help you predict what the weather will be like in one or two days’ time.

Clear liquid means fine weather. Large flaky crystals mean cloudy skies, unless they are fern-shaped, in which case they mean wind. Small dots indicate damp, foggy weather, a milky appearance warns of rain, and stars on a bright winter day foretell snow. You get the picture.

Even with the descriptions of what kind of crystals mean which kind of weather, I find using the storm glass to be a bit hit or miss. For example, I’ve been reading the crystals in the storm glass as being large and flaky, meaning clouds. But The Nine-Year-Old describes those very same crystals as fern-shaped, meaning wind. It’s hard to tell which of us is right, because we’re in Chicago in winter. Cloudy and windy? Must be a month containing the letter R.

So do storm glasses work at all?

My storm glass forecast on January 25, 2017. For the record, it was cloudy that day. (Photo: Shala Howell)

Cecil Adams of the Straight Dope has apparently done the definitive study on whether or not storm glasses work. Or rather, his assistants Una and Fierra did. Cecil just wrote it up.

Unwilling to shell out the $179 that novelty storm glasses were selling for at the time (October 2010), Una and Fierra built their own set of six storm glasses from scratch. Once the ingredients in the glass had settled and begun forming crystals, the two began an intensive 12-week program of watching crystals grow.

Their goal wasn’t to see if the storm glasses were accurate in predicting all kinds of weather. They simply wanted to know if the storm glasses could accurately predict rain. So every day for twelve weeks, they recorded the appearance of the crystal and whether or not it rained that day. (See Cecil’s article here for a more precise description of their experiment.)

At the end of the experiment they analyzed the data to see how good the storm glasses’ track record was. Answer: The accuracy of individual glasses varied. Some were slightly more accurate than others, but in general, the storm glasses accurately predicted rain about half the time.

If they are so useless, why were storm glasses invented anyway?

When storm glasses were invented in the 18th century, they were widely promoted as a more affordable weather divining tool for people whose lives depended on the weather, like farmers, fishermen, and sailors, but who couldn’t afford the more expensive (and more accurate) mercury barometers.

After a huge storm sank some 200 ships off the coast of the British Isles in October 1859, sea captain Robert Fitzroy pushed for Britain to establish a series of weather stations along its coast to monitor sailing conditions. The stations were equipped with storm glasses and sent reports of local conditions back to the Meteorological Office in London. The first weather reports based on this system began appearing in the Times in 1860. By 1861, local fishing ports had begun flying cones to alert sailors to approaching gales.

At first, merchants objected to Fitzroy’s weather forecasting system because it kept their sailors in port more often. But the fishermen themselves loved it, and credited Fitzroy with saving countless lives. The storm glasses Fitzroy championed in setting up this system were named after him, although it’s not clear that he himself actually invented them.

What is clear, however, is that Fitzroy recognized the unreliable nature of his weather prediction system. He exhausted his personal fortune in a futile effort to create a better one, before committing suicide in 1863.

The same storm glass as it appeared on the morning of February 2, 2017. You can see the crystals have dissolved some, only reaching to the top of the words “Rainy Weather.” It was cloudy that day too. (Photo: Shala Howell)

So if the storm glass isn’t responding to weather changes, what is driving the formation and dissolution of the crystals?

Although my storm glass hasn’t been much help for at-a-glance weather forecasts, the crystals inside it actually are growing and dissolving in response to some unseen environmental change. On January 25th, the crystals in my storm glass had expanded to touch the bottom of the words “19th Century.” By February 2, they had retreated to barely cover “Rainy Weather.”

Why?

There are lots of theories for what causes the chemicals in the storm glass to create a shifting array of crystal patterns. Early proponents of the storm glasses posited that the glasses responded to light, heat, wind, atmospheric pressure, or electrical charges in the air. But the truth is, no one really knows.

Pressure may have been a factor in the early storm glasses, which were sealed with flexible rubber caps, but it’s unlikely to have any impact on modern storm glasses, which come in hermetically sealed glass containers. The idea that the crystals are responding to electrical charges in the environment around them seems equally implausible, given that glass is an insulator, not a conductor of electricity.

Still, the other theories are intriguing and call for further investigation. This is the part where I tell you to hang on for a week, while The Nine-Year-Old and I perform some highly scientific yet completely safe to try at home tests. We’ll report back.

Note: Although most commercially available storm glasses are glass tubes, Weather in a Bottle has a set of lovely storm glasses that come in a flat round glass container.

Related Links:

- Can storm glasses predict the weather? (The Straight Dope)

- Storm glass: The mysterious weather-predicting fluid crystal (Science Blogs)

- Geek romance: How to make a storm glass pendant (Science Blogs)

8 Responses to ““How does a storm glass work?”: Part One, the Pondering”

[…] The Nine-Year-Old is on the first of her spring breaks and we’re filling the time with science. We’re almost done with the temperature segment of our Storm Glass Experiment Series. […]

LikeLike

[…] About two weeks ago, after noticing that our replica storm glass had been predicting cloudy skies more or less continuously since we acquired it six months ago, The Nine-Year-Old and I began to wonder how storm glasses worked. You can read our initial research on the topic here. […]

LikeLike

[…] “How do storm glasses work?” Part One: The Pondering (Caterpickles) […]

LikeLike

[…] “How do storm glasses work?” Part One: The Pondering (Caterpickles) […]

LikeLike

[…] “How does a storm glass work? Part One: The Pondering” (Caterpickles) […]

LikeLike

My friend has an old round storm glass bottle,that has red liquid in it,not the crystals,it has gotten”gunky”over the years and we need to know what the red liquid is so we can replace it,thank you

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by Caterpickles. I’m sorry for the delay in responding to you. My family and I were in the midst of moving from Chicago to California when you wrote in and this is the first day I’ve been able to work on the blog.

I’m no storm glass expert. I’ve never seen a storm glass with red liquid in it, so couldn’t tell you what that red liquid is.

However, Wikipedia tells me that the liquid in storm glasses is typically composed of a mixture of ingredients, including distilled water, ethanol, potassium nitrate, ammonium chloride, and camphor. You can read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm_glass.

I also found several recipes for liquid in storm glasses here: https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=ru&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fhimiklab.org.ua%2Fstormglass.shtml.

Perhaps one of those recipes includes a red liquid? Good luck. I’d love to know what you learn.

LikeLike

[…] 7. “How does a storm glass work? Part One: The Pondering” […]

LikeLike